The first time I learned about Lloyd Kahn was in this very magazine more than a decade ago, when he was presented with a Mother Earth News Lifetime Achievement Award. Alongside a photo of him at nearly 80 years old, skillfully skateboarding through San Francisco, was a description calling him “one of the world’s leading voices in creative, environmentally sensitive, human-centered building practices.” Intrigued by his adventurous and conscientious lifestyle, I picked up Kahn’s book Tiny Homes: Simple Shelter and was hooked — on the idea of living with less and loving it, and on the curiosity and encouragement at the heart of his books.

Twelve years later, Kahn continues living that lifestyle from Bolinas, California, where he resides in a home he and his wife, Lesley Creed, built up over the course of 50 years. I called him in fall 2025 to ask what advice he’d give to people who want to follow in his footsteps, whether they’re builders, homesteaders, or people who want to go against the grain. Here’s what he had to say.

Learn As You Go

Kahn didn’t follow a traditional path to being a builder, though he was involved in building projects from a young age. At 12, he helped his dad build a house in the Sacramento Valley. Under the hot California sun, the builders outfitted young Kahn with a carpenter’s belt and a hammer and nails and assigned him to nail on the sheathing. “And so I got up there and started doing that. And I really liked it. It just was something natural. I found I could work with my hands, and I liked the smell of wood, and I liked the feeling of getting something accomplished,” he says. At 18, he worked as a carpenter on the docks in San Francisco. Then, a stint in the Air Force and a handful of years as an insurance broker took him away from building, to which he returned in the ’60s when the countercultural revolution was underway. He eventually built four houses, ending with the home in Bolinas.

A decade of carpentry laid the foundation for his work in publishing. He became the shelter editor for the Whole Earth Catalog in 1970 and launched Shelter Publications in 1973, through which he ultimately published more than a dozen books on building.

But he wasn’t a building expert right away. Kahn’s first project after returning to building was transforming a carport into a studio with a sod roof in Mill Valley. “I just started building, and I had kind of the rudiments of building I knew about, but I learned something then that I’ve employed in a lot of things in life since then: If you don’t know what to do, start, and you’ll figure it out as you go.” And while he laments not learning some of the finer arts of carpentry, “I got a lot of building done that I wouldn’t have if I’d waited around until I was a highly skilled carpenter,” he says.

Live Thrifty

Throughout his building career, Kahn salvaged used materials wherever he could get them. He’d often buy up used wood from the Cleveland Wreckers, a wrecking company in San Francisco. For his house in Big Sur in the ’60s, he used materials from a torn-down farm labor camp in Salinas. Wood salvaged from a horse stable in San Francisco became girders in his Big Sur home. And the siding and shakes on that house came from the nearby woods, “where the loggers would leave behind any redwood that was less than 8 feet long. And so if you went into the woods with a chainsaw, you could cut out bolts from those trees and split them in with a thing called a froe, which is kind of like a big machete with a handle, hitting it with a bowling pin. You split the shakes. And so that was a way to get free wood.”

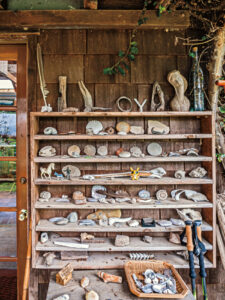

And when he moved to Bolinas, he would scour the countryside for old barns and chicken coops and talk to the farmers about tearing them down and using the materials. “A lot of times, they were just glad to get rid of them,” he says. He also got to know George Taylor, a Navy veteran who was tearing down Navy barracks on Treasure Island, a former naval station. “So, I bought a lot of the materials. In fact, this room I’m sitting in right now is pretty much entirely built of used materials from George Taylor,” he says. And almost all of the windows in his Bolinas home are used, many of them from old chicken coops. For Kahn, it was an aesthetic decision as well as a thrifty one: “I’ve always liked the looks of used wood. … So, I got used things whenever I could.”

Keep It Simple

Kahn got into geodesic domes in 1968, building these experimental structures and releasing Domebook One and Domebook 2. Now, he’s in an era of “rediscovering rectangles.” When asked what he’d do differently in his building career, he said, “I wouldn’t spend five years with circle madness. … I would rather look at what’s been done before, and especially see what farmers have done, because they have to be practical. And so I would do everything differently, but at the same time, I’m happy with where I am, mistakes and all, because it’s just where I’m at today. So, I can’t go back in time.”

On the other side of “circle madness,” Kahn has been struck by the simplicity of traditional homes, chicken coops, and barns. With roofs resting over vertical walls, such structures are easy to waterproof. Rectangular furniture, such as beds, refrigerators, and chests of drawers, fit neatly inside. And you can easily subdivide and expand rectangular shelters. “I was looking at these buildings and thinking, that’s so simple. … So, I got around to thinking that rather than starting out with an abstract concept — like you want to build a seven-sided house, you want to build a dome, you want to build an elliptical form — that you could stick with the rectangles and use the materials that you want to live with and get it done as quickly and economically as possible, and then get on with your life. Me, I don’t want to spend my life building. If you do get away from rectangular construction, it’s going to take you a lot more time and a lot more money. And that’s okay, because there are people who want to do that, but not me. I want a house as a shelter. I wanted to keep the rain off and to keep warm on cold nights, to be able to sleep and eat and get healed. And so I went out on a journey of trying out a lot of different things and discarded a lot of them, and got back to — at least as far as the form of construction goes — standard construction.”

So, for anyone embarking on building their own home, Kahn recommends keeping it “small and sensible,” with a core in which you have house heating, water heating, a kitchen, and a bathroom. “Build the house so that you can add on later on, but get the central part built and live in it, and then you don’t have any rent to pay. And maybe you’re going to have to get a mortgage, and maybe you’re going to have to hire some professional help, but, you know, do what you can.”

Do What’s Possible, Not What’s Perfect

“Do what you can” is pragmatic advice that combines his years of experience with the realities of today. Kahn acknowledges that what was possible for him and his wife may not be as achievable now. When he got his start, he says, “you could live on so little money. I mean, Lesley and I, when we got together, we were living on $300 a month. You could get by. And needing so little meant that you had time. And, of course, now, everything is so expensive, and it’s just a different era. … In my town, teardowns are a million dollars. A water meter is over $200,000. My water meter was $250. And septic systems are [up to] $80,000. Mine, a gravity system, was $3,000, and it’s working fine, with periodic maintenance, some 50 years later. So costs are just enormous nowadays.” Plus, Kahn built his home during an era of less-restrictive codes and far fewer people.

So, he says, you may have to go about it a different way. “If I were in my 30s or so, a young person, instead of trying to find 10 acres in the country and building a log cabin or an adobe house or harvesting all the wood on your own property, look in towns and cities in a distressed area … find a rundown, inexpensive house that has a good foundation, but it needs other work. The advantage there is you’ve already got a water utility, electricity, and sewage.” From there, “do what you can with your hands. Maybe you get an apartment, maybe you get a loft in the city and fix it up, or maybe you get a school bus, which makes a good home to live in for a while while you figure out what to do. If you’re living in an apartment in New York City, grow some parsley on your fire escape. “

Living on less — whether less money or less space — remains an essential part of achieving this dream. “I tell young people, save enough money — so you can take a year off, and during that year, build a house, and then go back to your job or find a new job.”

Do It Yourself …

Looking back on building his homes, Kahn says, “I think the reason that I did all that was I just wanted to have a place to live. And if we’d been able to find a really nice house for a reasonable price, I don’t know if I ever would’ve started building, but that wasn’t the case. So, in order to have what I wanted, in terms of design, and especially in terms of materials, I had to do it myself. And the other aspect of it was to save money, because they figure a home is maybe 50 percent materials and 50 percent labor. So you’re saving 50 percent to start off with.”

With the advent of technology and AI, Kahn sees stability for people willing to work with their hands. “What’s happening is that the trade schools are booming right now. You’re still going to need carpenters and plumbers and electricians.” He envisions a young builder equipped with tools who “goes around and works for people doing remodels and maybe even building a house from scratch. In our town, there are a few guys like that, and they’re very much in demand. Not a contractor, but a builder. So that’s something that a young person could do now, learn a trade, and then you’ll find that people want your services.”

While he enjoys using technology himself to capture his curiosities and share them on his Substack and Instagram, he recommends, “In this day and age, do what you can yourself — use your hands — a computer is not going to build a home for you, you know. You still need human hands, and you still need a hammer and a saw — even if the hammer is a nail gun and the saw is electric — and so I think that those kind of things are still valid. And maybe even more so nowadays, because it’s a break from the technological world we’re all immersed in.”

… But You Can’t Do It All

But even for those who set out to do it themselves, Kahn challenges the myth of being completely self-sufficient. “It just doesn’t make sense to try to do everything. So, it’s like perfection. You never get there, but you work towards it. Do as much stuff for yourself as possible. … I’d get help where I needed to.” In the 1970s, Lloyd and Lesley and three or four other couples in Bolinas were living the homesteading life. “We were trying to see how much of our own food we could provide. And that’s when I concluded that you couldn’t do everything. Say you grow corn or potatoes or zucchini, you just take the vegetable from the garden and eat it. But if you grow wheat, you have to harvest the wheat, then set it in the field to dry, then thresh and winnow it to separate the grain from the chaff. Then you have to grind it. And so there’s about five steps before you get flour. And so, you know, it didn’t make sense to do that, and we figured that out pretty quickly. But again, we just did what we could.”

Still, little by little, Lloyd and Lesley put decades of care into the homestead and its soil, and now the garden generates food without requiring much input. Kahn puts about three or four hours a week into his garden and yields more than half of the vegetables he eats, including kale, chard, asparagus, artichokes, strawberries, raspberries, peas, zucchini, yellow-neck squash, and peppers. “I’m eating more out of the garden than I ever have before, and part of that is because we’ve been on this piece of land for 50 years, and the soil is really good, and we’ve got raised beds with wire underneath for the gophers,” he says.

Prioritize Your Health

Alongside books about shelter, Kahn’s publishing company also released books about stretching and running. Exercise and diet have been central to Kahn being able to maintain a homestead, travel, and even skateboard into his 90s.

The Half-Acre Homestead mentions one of Kahn’s heroes, Alan Chadwick, and how, for him, “beauty was an uplifting spiritual force that carried within it the ability to heal human souls that had become estranged from nature.” About this quote, Kahn says Chapman gave a talk one day that changed his world. “He talked about plants, and that if a plant was in tune with all the forces, the soil, the air, the water, and the sunshine, that it would be strong and it would resist disease, but if the plant had something wrong with it, that’s when the aphids are going to attack. And I think that that’s the case with human beings. … So, I think that whatever you can do to stay healthy and exercise is a huge part of that, and diet is another huge part of that, is a way to connect with — I don’t know if I’m comfortable with the word ‘spiritual’ — but with forces that are outside of the ordinary, and maybe forces that can’t be scientifically quantified, things that you can’t observe.”

Embrace ‘Imperfections’

Kahn’s wife, Lesley, died in 2024. About this loss, he simply quotes William Blake: “‘The busy bee has no time for sorrow,’ so I’m keeping busy.” Kahn says their book The Half-Acre Homestead is “actually a love letter to her. It’s all about her, about her garden and her weaving and quilting, and all the things that she did, and all the things we did from scratch around here.”

And he spoke admiringly of the anomalies in her quilts. “The irregularities, I think, are the art. … And so in her quilts, where she would break from strict engineering regularity, and she’d have an eight-pointed star, and she’d run out of yellow fabric, she’d make one point of the star smaller than the other points. If you look at her quilts, you see those irregularities, and they’re what give those things their charm.”

Some Things Change, Some Stay the Same

“Once in a while, I get this feeling that maybe this is the best time to be alive, that it’s exciting,” Kahn says. “And one of the things about being 90 years old is that I have a long period of time to look back upon. It’s fascinating to have lived through these eras. I mean, in the mid-’50s, there were 13 million people in California. Now, there are 40 million people. … And when I was born, in 1935, there were only 5 million people in California. We had the whole place to ourselves! So that’s kind of an advantage of being old — being able to look back upon all those very different times. I do find the world nowadays fascinating. And sure, there’s a lot of bad shit going on, but once in a while, I’ll walk out and I’ll see a crescent moon, and I’ll think it’s amazing, that it’s so beautiful, or the ocean is still there, you know? And in these turbulent times, there are certain things that are still there.”

Lloyd Recommends

Cool Tools by Kevin Kelley

Life-Changing Homes by Kirsten Dirksen and Nicolás Boullosa

Amanda Sorell is a storyteller who lives in Seattle. She’s an editor for Mother Earth News and is passionate about food access and foraging. Read her newsletter at eClips.Substack.com.