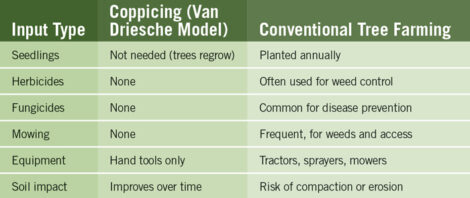

Coppicing Christmas trees is a sustainable way to grow trees, rather than the conventional approach of mowing, herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides.

A Quick Coppicing Guide for Beginners

Coppicing is the practice of cutting a tree or shrub to stimulate regrowth from the stump or base.

Best For

- Small acreages

Benefits

- Regrows without replanting

- Improved soil health

- Supports biodiversity

- Generates kindling, greens, craft wood, and marketable trees

In a snowy hollow in Ashfield, Massachusetts, 10-acre Pieropan Christmas Tree Farm is challenging conventional wisdom on how evergreens can be grown sustainably. It’s not blanketed in plastic mulch, nor do diesel tractors churn through rows of tightly sheared trees. Instead, the farm hums with biodiversity, footsteps, and a pair of loppers. And at the heart of it all is farmer, craftsman, and spoon carver Emmet Van Driesche.

Through a centuries-old technique known as “coppicing,” Van Driesche and a growing number of small-scale tree farmers are reviving a model that offers both ecological resilience and economic opportunity – without pesticides.

What’s Coppicing, and Why Should We Care?

Coppicing is the art of repeatedly harvesting trees by cutting them down to a stump and allowing them to regrow. While the practice has roots in centuries-old woodlots, for firewood and basketry, Van Driesche has adapted it to modern tree farming.

Unlike conventional systems where stumps are ripped out and seedlings replanted, a single coppiced stump may produce usable trees for decades. “Coppicing is any situation where you’d cut a tree above the ground, where the intent is for it to regrow,” he explains. “With Christmas trees, you cut the tree about waist- or chest-high, leaving a few layers of live branches below. That keeps the stump alive, causing it to throw out new shoots.”

Each stump can produce dozens of leaders (the topmost shoot that forms a tree’s shape), but not all are created equal. Some will put on just 4 inches of growth per year. “Others grow nearly a foot,” Van Driesche says. “So you select the strongest, give them space, and in 3 to 4 years, you’ve got another marketable tree.”

A Nearly Forgotten Practice

The practice of coppicing for holiday trees thrived briefly in the early 1900s. Initially, most trees were simply harvested from natural woodlots. But from the 1920s to the 1950s, some tree farmers noticed something intriguing. “A farmer near here saw that when he left stumps with live branches below the cut, they regrew,” Van Driesche says. “It spread coast to coast. But by the 1950s, economics had shifted. Tree farming moved to old pastureland, where you could run tractors, plant rows, and spray for weeds.”

Today’s conventional tree farms often rely on frequent mowing, herbicides to control weeds, and applications of fungicides and insecticides to keep the trees alive and thriving. Van Driesche’s farm couldn’t be more different.

According to North Carolina’s state extension, common inputs on holiday tree farms include glyphosate-based herbicides, chlorothalonil to prevent needle cast fungus infection, and bifenthrin to suppress insect pests, such as spruce beetles.

A Multitude of Benefits

Perhaps the biggest innovation of coppiced farming isn’t technical – it’s philosophical. At the farm, coppicing becomes a tool to turn marginal land into multiuse, resilient woodland.

“It’s a good way to use rocky hillsides or to convert naturally occurring balsam forests,” Van Driesche says. “We don’t plant seedlings. We don’t yank stumps. We just work with what’s there.”

That means embracing the natural order. “You’re constantly dancing with what the tree wants to do,” he laughs. “You don’t coddle anything. You cut away what’s not useful and let the best growth rise.”

This relationship with the land also yields surprising side benefits. By cutting back the lower “skirts” of the stumps and pruning trails every few years, Van Driesche harvests tons of greens that are bundled for wreaths – an income stream that rivals tree sales. “We tie 600 wreaths a year and sell tons of greens to other wreath-makers. Nothing goes to waste.”

Van Driesche explains that about 95 percent of the holiday trees grown on the farm are balsam fir, with smaller numbers of Norway spruce, white pine, and a few other spruce species. The farm’s founder, Al Pieropan, started thousands of trees over a 12-year period by thinning and hand-gathering wild seedlings in gunnysacks and planting them 50 at a time. Although other species were planted early on, balsam fir quickly gained favor for whole trees and cut greens.

“Balsam became what people wanted for Christmas trees … and it’s continued to be what people want,” Van Driesche says.

The same is true for wreath-makers‘ preferences. Balsam’s popularity stems largely from the aroma – ”one that smells like Christmas.”

No Tractor? No Problem.

Conventional growers often use mowers, sprayers, and planters to manage fields. At Pieropan Farm, those machines are replaced by one very determined human and a pair of loppers.

“Everything on the farm is done by hand,” Van Driesche says. “I use a pickup truck to move bales or trees, but otherwise, no machinery.”

That may sound daunting, but Van Driesche has embraced seasonal intensity in exchange for annual freedom. “I do all of the farmwork in November and December. The rest of the year, I don’t even visit. I live 10 minutes away, and the farm just does its thing.”

That rhythm gives him the capacity to focus on a second passion: carving wooden spoons and running a global craft business 10 months of the year.

Diversifying the Farm, from Growing Trees to Carving Spoons

When Emmet Van Driesche began to carve wooden spoons over a decade ago, it wasn’t out of artistic ambition – it was holiday pragmatism. “I started carving spoons 12 years ago as a way of having something else to sell at the Christmas tree farm,” he recalls. “You have this audience of people showing up, and it’s the time of year they want to buy something as a gift or to put in a stocking.”

That first batch of simple spoons – carved during the off-season from branches pruned from his 10-acre balsam firs – quickly took root in something deeper. Over time, spoon carving evolved from a seasonal craft into a full-blown second career.

“It turns out that I really love doing it,” Van Driesche says. “I’ve been lucky enough over the last 10 years to turn it into what I do the rest of the year.”

Increasingly, small farmers are looking for ways to diversify their income streams and fill their downtime. During the harvest months of November and December, Van Driesche is all-in for the holidays: pruning, bundling, and greeting generations of families who come to cut their own tree. But for the other 10 months of the year, his workshop hums with the sound of wood against knife. He carves each piece from greenwood – fresh-cut branches – which he carefully shapes and dries into elegant, durable utensils.

Part of what makes his spoons so appealing is that they don’t hide their handmade nature. Unlike machine-produced utensils, his pieces reflect the unique curvature and grain of the branches they came from. Their organic shape is intentional, celebrating imperfections and the quiet process of making something useful and beautiful.

In many ways, Van Driesche’s approach to carving spoons mirrors his philosophy as a coppiced-tree farmer: Work with what the land gives you, respect the rhythms of nature, and keep your hands in the process.

“They’re both about working with what you’ve got – what the land or the wood wants to be,” says Van Driesche.

A Hands-On Legacy and Labor

By thoughtfully marketing what his scrappy 10 acres have offered him – and even expanding into a second business that fits with the seasonality of the first – Van Driesche has managed to make a living and do the work he enjoys.

Still, coppicing isn’t a walk in the woods. It requires planning, physical labor, and a long-term mindset.

“When you cut branches to clear paths or prepare greens, you’re bundling 50-to-70-pound bales and hauling them – sometimes on your back down a hill,” Van Driesche says. “There’s no way around the physical work.”

Yet he’s learned to make it manageable. “The guy before me used a 10-foot pole pruner you had to raise overhead to snip branches,” he says. “I switched to shears, then eventually just stopped shearing at all. I let the trees grow naturally, and customers love the aesthetic.”

Trees That Train Their Customers

While some worry that customers might cut down the wrong trees or damage the stumps, Van Driesche says the farm’s design teaches people what to do.

“I used to explain to people how to leave the stump,” he says. “Then I realized – I can prune the tree so that a clear ‘stem’ is visible. People naturally cut at the right spot without needing instructions.”

This subtle guidance not only supports the regrowth cycle, but also reinforces the farm’s low-maintenance model. “The trees show people what to do. The landscape is the teacher.”

Sustainability: A System Built on Soil and Stumps

From an environmental perspective, coppicing has a number of benefits. With no tilling, spraying, or annual replanting, the carbon footprint of the farm is reduced, when compared with a traditional holiday-tree model. Decades of dropped foliage and decomposing brush have restored once-depleted soil and allowed the trees to continue to regrow new shoots.

“We’re essentially doing permaculture chop-and-drop – just letting material rot in place,” Van Driesche explains. “Even though we export a lot of biomass, a lot is produced and left behind too.”

Because the site is a patchwork of ages, species, and habitats, it sidesteps the vulnerability of monoculture.

“We’re creating an understory forest with different species. There’s mature forest on all sides. That diversity protects against pests, drought, and die-offs,” he says. “I think I saw two dead trees all year.”

Compare that with seedling-based farms, which can see substantial mortality year to year and depend on chemical treatments to help prevent it.

Is Coppicing Right for Your Land?

Can you coppice holiday trees in your backyard? Maybe not to Van Driesche’s scale, but the same principles apply.

“Coppicing works great for marginal land – rocky, sloped, or less accessible spots where conventional methods won’t work,” he says. “You don’t need much machinery. You don’t need frequent inputs. You just need time, patience, and pruning shears.”

Even a quarter-acre stand of conifers can yield kindling, wreath materials, and eventually marketable trees if managed right. And for growers already in the business, incorporating coppicing offers diversity in timing and age structure that can buffer against market swings.

“You can harvest a mature tree from a stump, and still have a younger one coming along on the same root system. Done well, you shorten the turnaround time.”

While you can’t pack coppiced trees as tightly as conventional rows, the efficiency of reuse and multistage growth closes the gap – and may beat it when you consider all the usable material.

The Beauty of Slow Growth

Despite coppicing’s many merits, Van Driesche admits the method isn’t for everyone. It requires a hands-on approach, and the trees don’t always conform to showroom symmetry. But that’s part of the charm.

“What I’ve come to realize is that it’s an aesthetic choice,” he says. “Some people want the perfectly sheared tree, and there are farms that do that. But our customers like the experience of wandering through a managed forest. They come back year after year.”

Advantages of Natural Trees

According to the American Christmas Tree Association, “99 percent of consumers intend[ed] to display at least one Christmas tree in their homes [in 2024].” It also reports that 25 to 30 million real trees are sold every year.

Besides choosing to purchase a product that’s produced in the U.S., unlike the 10 million artificial trees sold every year – 90 percent of which come from China – real trees have the advantage of being biodegradable, which avoids adding to landfills.

While some may opt for a living tree that can be replanted after the season ends, not everyone has the ability to replant a living tree. In addition, because these coppiced trees can be grown without herbicides, they can be fed to animals, such as goats, sheep, and alpacas, after the season ends and the holiday tree is undecorated and taken down.

With U.S. consumers purchasing millions of live trees each year, perhaps it’s time to expand the availability of coppiced options. Because of the growing desire of many consumers to return to “natural” processes, coppicing’s time may be coming again.

“We’ve basically forgotten that you can do this,” says Van Driesche. “But it works. And it’s worth remembering.”

Coppicing Versus Conventional: The Inputs Breakdown

Kenny Coogan earned a master’s degree in global sustainability and co-hosts the “Mother Earth News and Friends” podcast. He also created and hosts the TV show Florida’s Flora and Fauna with Conservationist Kenny Coogan.

Originally published in the December 2025/January 2026 issue of MOTHER EARTH NEWS magazine and regularly vetted for accuracy.